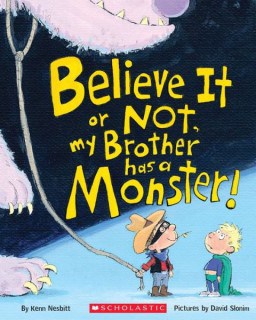

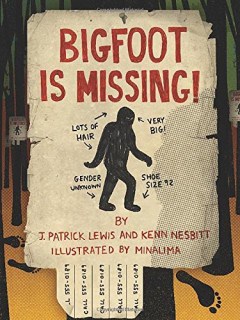

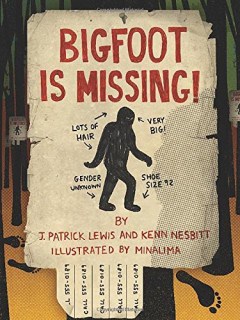

Today is the birthday of my newest book, Bigfoot Is Missing!, co-authored with former Children’s Poet Laureate, J. Patrick Lewis. Pat and I had a terrific time researching cryptids (creatures whose existence has not yet been proven) from around the world and writing the poems for this collection. And we were thrilled at the selection of Minalima Design to illustrate the book.

Minalima, the design team of Miraphora Mina and Eduardo Lima, are perhaps most well-known for creating the graphic props — such as posters, newspapers, maps, etc. — for the Harry Potter films, making them a perfect choice for this “mischievous and slighly edgy” collection of poems about the creatures of shadowy myth and fearsome legend.

Bigfoot, the Mongolian Death Worm, and the Loch Ness Monster are among the many creatures you will find within the pages of this large picture book. Don’t be surprised if you have to look twice—the poems in this book are disguised as street signs, newspaper headlines, graffiti, milk cartons, and more!

Publisher’s Weekly gives Bigfoot Is Missing! a starred review, saying, “These brief, playful poems will whet readers’ appetites to learn more about bunyips, luscas, and Mongolian death worms. Luckily, endpages supply legends and details about these and other creatures, including where they can—or rather can’t—be found.”

Here are links to a few of the rave reviews for Bigfoot Is Missing!

Also, the publisher, Chronicle Books, has a Poetry Picture Book Teacher Guide here with Common Core connections for Bigfoot Is Missing! and several other poetry books.