A video poetry-writing lesson

Acrostics are one of the easiest forms of poetry to write because they just have a single rule and they don’t have to rhyme. In this video lesson, I show how you can create your own acrostic poems in just a few steps.

Acrostics are one of the easiest forms of poetry to write because they just have a single rule and they don’t have to rhyme. In this video lesson, I show how you can create your own acrostic poems in just a few steps.

Acrostics are a fun poetic form that anyone can write. They have just a few simple rules, and this lesson will teach you how to create acrostic poems of your own.

To begin with, an acrostic is a poem in which the first letters of each line spell out a word or phrase. The word or phrase can be a name, a thing, or whatever you like. When children write acrostics, they will often use their own first name, or sometimes the first name of a friend.

Usually, the first letter of each line is capitalized. This makes it easier to see the word spelled out vertically down the page.

Acrostics are easy to write because they don’t need to rhyme, and you don’t need to worry about the rhythm of the lines. Each line can be as long or as short as you want it to be.

To create an acrostic, follow these five easy steps:

Now let me show you how to follow these steps.

The first step is to decide what you would like to write an acrostic poem about. I recommend you start by writing an acrostic based on your name or on your favorite thing, whatever that happens to be. It doesn’t matter if your favorite thing is soccer, video games, chocolate, music, pizza, movies, or anything else.

For example, I especially like ice cream, so I decided to write an acrostic about ice cream. Begin by writing the word “ICE CREAM” down the page like this:

I

C

E

C

R

E

A

M

Next, you want to say something about ice cream in each line. A good way to do this is to “brainstorm” lots of ideas. I wrote down a list of all the ice cream flavors I could think of, including chocolate chip, strawberry, rocky road, and others. Then I put them in a list wherever they would fit, like this:

Ice Cream

I

Cookies & Cream.

English Toffee.

Chocolate Chip.

Rocky Road.

E

Almond Fudge.

M

You’ll notice that I didn’t fill in all of the lines. That’s because I couldn’t think of a flavor that started with “I” and I could only think of one flavor that started with “E.” Also, I thought I would do something different with the last line, to make it an ending for the poem, rather than just another flavor.

Finally, I filled in the missing lines, like this:

Ice Cream

I love every flavor.

Cookies & Cream.

English Toffee.

Chocolate Chip.

Rocky Road.

Even Strawberry and

Almond Fudge.

Mmmmmmmm.

Now, just as you can write acrostics about things you like, you can also write them about things you don’t like, such as chores, homework, and so on. Here is an example acrostic about homework.

In addition to writing about things you like, such as ice cream, you can write acrostics about things you don’t like. For example, if you don’t like homework, you might try writing a poem about it. Begin by writing the word “HOMEWORK” down the page:

H

O

M

E

W

O

R

K

Next, brainstorm as many words and phrases as you can think of. Here are some I came up with:

Reading for hours. Writing. Not my favorite. Every Day. I’d rather be watching TV. Makes me crazy. Overwhelming. Hard to do.

Notice that some of these words and phrases begin with the letters in the word “homework.” I put these ones in where I saw they would go:

Homework

Hard to do

Overwhelming,

M

Every day

Writing

O

Reading for hours.

K

Finally, I found a way to fill in the rest of the words, and even give it an ending. Here is the finished acrostic:

Homework

Hard to do and sometimes

Overwhelming,

My teacher gives us homework

Every single day!

Writing for hours

Or

Reading for hours.

Kids need a break!

Here’s one more acrostic poem I created recently with the help of kids from all around the country during an online author visit:

Minecraft

Minecraft.

I love it.

No doubt about it.

Exploring, building, fighting

Creepers, zombies, and skeletons.

Roaming around for hours.

A

Fun

Time for everyone!

Here are a few things to remember as you begin writing your own acrostics:

Finally, remember, acrostic poems are one of the easiest and most fun ways to create poems of your own. Give it a try and see what you can come up with.

Today, we’re embarking on a journey into the world of “alphabet poems.” If you’ve enjoyed creating acrostic poems, where the first letters of each line spell out a word or phrase, you’re going to love alphabet poems!

In alphabet poems, each line starts with a different letter of the alphabet, following the order from A to Z. It’s like weaving a magical tapestry with words, where every letter is a new stroke of your imagination. Imagine combining the fun of acrostics with the thrill of exploring the entire alphabet! So, let’s get our pencils ready and explore every letter in a new and exciting way with alphabet poems!

What is an Alphabet Poem?

An alphabet poem is a playful and creative way to use the ABCs in poetry. Just like in acrostic poems, where the first letters of each line spell out a word, in alphabet poems, each line starts with the letters of the alphabet, in order.

Starting with A and ending with Z, each line of the poem begins with the next letter in the alphabet. This creates a fun challenge: you get to think of a word or idea that starts with each letter. It’s like a puzzle where each piece is a letter that helps to build a beautiful picture with your words.

For example, if you’re writing about nature, your poem might start with A for ‘Autumn leaves,’ then B for ‘Breezes blowing,’ and so on. The challenge is to connect each line in a way that tells a story or paints a picture, making your way from A to Z.

Alphabet poems are not just fun; they’re a great way to learn new words and think about how to fit ideas together in creative ways. Ready to give it a try? Let’s find out more about why writing alphabet poems is not only enjoyable but also a great exercise for your brain!

How to Write Your Own Alphabet Poem

Writing an alphabet poem is like going on a treasure hunt with letters! Here’s how you can create your very own:

1. Choose a Theme: Start by picking a theme you love – it could be animals, your family, outer space, or even your favorite hobby. This theme will guide your poem from A to Z.

2. Start with A and Continue Through Z: Begin your poem with a word or idea that starts with A. For example, ‘A is for Apples, red and bright.’ Then move on to B, like ‘B is for Berries, sweet and light,’ and keep going through the alphabet.

3. Be Creative with Challenging Letters: Letters like Q, X, and Z can be tricky, but they’re also a chance to be extra creative! For Q, you could write ‘Quiet nights with twinkling stars.’ For X, think outside the box – ‘Xylophone tunes ringing clear’ or use words that start with an X sound, like ‘eXtraordinary day.’ And for ‘Z,’ try something like ‘Zebras racing in my dreams.’

4. Connect Your Lines: Try to make each line connect to the next in some way, either through rhyme, rhythm, or a continuing story or theme. This will make your poem flow nicely.

5. Have Fun and Experiment: The most important part is to have fun and play around with words and ideas. Alphabet poems are a great way to experiment with language and see where your imagination takes you.

Here’s an example of how the beginning of an alphabet poem with an animal theme might look:

A is for Ants, marching so small,

B is for Butterflies, fluttering tall,

C is for Cats, stretching their claws,

D is for Dogs, pointing their paws,

Or you might simply use words that start with each letter. Here’s the beginning of an alphabet poem with a nature theme:

Arctic snows are white and cold.

Beaches’ sands are warm and gold.

Caves are chambers underground.

Deserts have cactus all around.

Remember, there’s no right or wrong way to write an alphabet poem. They don’t even have to rhyme! It’s all about exploring words and having fun with the letters of the alphabet.

Time to Write!

Now that you’ve explored the exciting world of alphabet poems, it’s time to put pencil to paper and create your own. Remember, each letter in the alphabet is like a key, unlocking your imagination and creativity. As you write your alphabet poems, you’re not only having fun with words, but you’re also learning and growing as a writer.

Don’t worry if some letters seem hard at first. Every poet faces challenges, and it’s all part of the adventure. The most important thing is to enjoy the process and see where your creativity takes you.

So, keep playing with words, experimenting with ideas, and most of all, keep enjoying the wonderful journey of poetry. We can’t wait to see the amazing alphabet poems you create. Each one will be as unique and special as you are!

Happy writing, and may your alphabet adventures be filled with fun and discovery!

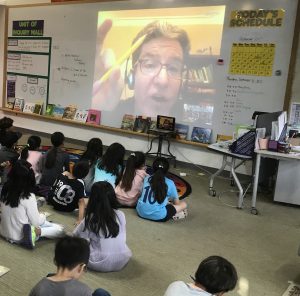

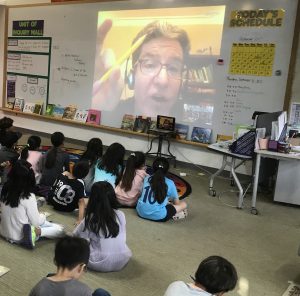

Throughout the school year, I visit many, many schools around the world virtually through Zoom, Meet, Teams, Skype, etc. In other words, I can visit your class or your school online whenever it’s convenient for you, for a fee.

However, if your class or school would like to visit with me, but you don’t have a budget for virtual field trips, I also provide webinars in conjunction with Streamable Learning, the leading provider of interactive livestreams in the K-12 market in the US and Canada. Through quality educational content and an easy-to-use platform, Streamable Learning aims to in introduce interactive livestreams as a valuable supplemental tool for classrooms and families seeking to inspire and educate their K-12 students.

During the 2023-24 school year, I will be doing more than a dozen online webinars, including interactive poetry-writing lessons and programs on famous children’s poets from Dr. Seuss to Shel Silverstein. Schools are invited to join any of these sessions for free as my guest.

Streamable Learning offers a convenient, cost-effective, and comprehensive calendar of interactive livestreams delivered by subject matter experts and designed to supplement your existing and future lesson plans. To discover hundreds of engaging, educational programs, have a look a their Livestream Calendar.

Streamable Learning offers a convenient, cost-effective, and comprehensive calendar of interactive livestreams delivered by subject matter experts and designed to supplement your existing and future lesson plans. To discover hundreds of engaging, educational programs, have a look a their Livestream Calendar.

I have been offering interactive poetry livestreams through Streamable Learning for several years now, and I hope you’ll be able to join me this year. You can register and participate in as many of these upcoming sessions as you like.

If you would like to attend one of my programs, please see the list of registration links shown below. When you click on the link, you will need to fill out just a few items and once you have finished the form, you will then receive an email with the livestream link. If you do not, please check your spam folder. It is possible that the livestream link will end up there. To join the program, you will need to download the Zoom app. You can download this free app at www.zoom.us/download and click on “Zoom Client for Meetings.” If you have any difficulty, contact efriedman@streamablelearning.com.

September 25, 2023

March 1, 2024

March 21, 2024

April 1, 2024

April 17, 2024

May 9, 2024

June 3, 2024

If you would prefer to arrange a private interactive videoconference for your class or school only, simply click here to schedule an online author visit. I look forward to seeing your students online!

For several years now I have been doing live, interactive webinars in conjunction with Streamable Learning, the leading provider of interactive livestreams in the K-12 market in the US and Canada. Through quality educational content and an easy-to-use platform, Streamable Learning aims to in introduce interactive livestreams as a valuable supplemental tool for classrooms and families seeking to inspire and educate their K-12 students.

For several years now I have been doing live, interactive webinars in conjunction with Streamable Learning, the leading provider of interactive livestreams in the K-12 market in the US and Canada. Through quality educational content and an easy-to-use platform, Streamable Learning aims to in introduce interactive livestreams as a valuable supplemental tool for classrooms and families seeking to inspire and educate their K-12 students.

During the 2020-21 school year, I will be providing 27 online webinars, including interactive poetry-writing lessons, holiday poetry sessions, and programs on famous children’s poets from Dr. Seuss to Shel Silverstein. Schools are invited to join any of these sessions as my guest.

If you haven’t yet used Zoom, I think you’re going to love it. Zoom is a free videoconferencing program similar to Skype, but with clearer, more reliable audio and video.

If you haven’t yet used Zoom, I think you’re going to love it. Zoom is a free videoconferencing program similar to Skype, but with clearer, more reliable audio and video.

Streamable Learning offers a convenient, cost-effective, and comprehensive calendar of interactive livestreams delivered by subject matter experts and designed to supplement your existing and future lesson plans. To discover hundreds of engaging, educational programs, have a look a their Livestream Calendar.

I have been offering interactive poetry livestreams through Streamable Learning for several years now, and I hope you’ll be able to join me this year. You can register and participate in as many of these upcoming sessions as you like.

If you would like to attend one of my programs, please see the list of registration links shown below. When you click on the link, you will need to fill out just a few items and once you have finished the form, you will then receive an email with the livestream link. If you do not, please check your spam folder. It is possible that the livestream link will end up there. To join the program, you will need to download the Zoom app. You can download this free app at www.zoom.us/download and click on “Zoom Client for Meetings.” If you have any difficulty, contact efriedman@streamablelearning.com.

September 15, 2020

September 17, 2020

October 27, 2020

October 28, 2020

October 29, 2020

November 17, 2020

November 19, 2020

December 21, 2020

December 22, 2020

January 19, 2021

January 21, 2021

February 8, 2021

February 9, 2021

February 12, 2021

March 2, 2021

March 4, 2021

April 6, 2021

April 13, 2021

May 11, 2021

May 13, 2021

June 4, 2021

If you would prefer to arrange a private interactive videoconference for your class or school only, simply click here to schedule an online author visit. I look forward to seeing your students online!

For several years now I have been doing live, interactive webinars in conjunction with Streamable Learning, the leading provider of interactive livestreams in the K-12 market in the US and Canada. Through quality educational content and an easy-to-use platform, Streamable Learning aims to in introduce interactive livestreams as a valuable supplemental tool for classrooms and families seeking to inspire and educate their K-12 students.

For several years now I have been doing live, interactive webinars in conjunction with Streamable Learning, the leading provider of interactive livestreams in the K-12 market in the US and Canada. Through quality educational content and an easy-to-use platform, Streamable Learning aims to in introduce interactive livestreams as a valuable supplemental tool for classrooms and families seeking to inspire and educate their K-12 students.

During the 2019-20 school year, I will be providing 35 online webinars, including interactive poetry-writing lessons, holiday poetry sessions, and programs on famous children’s poets from Dr. Seuss to Shel Silverstein. Schools are invited to join any of these sessions as my guest, completely free of charge.

If you haven’t yet used Zoom, I think you’re going to love it. Zoom is a free videoconferencing program similar to Skype, but with clearer, more reliable audio and video.

Streamable Learning offers a convenient, cost-effective, and comprehensive calendar of interactive livestreams delivered by subject matter experts and designed to supplement your existing and future lesson plans. To discover hundreds of engaging, educational programs, have a look a their Livestream Calendar.

I have been offering interactive poetry livestreams through Streamable Learning for several years now, and I hope you’ll be able to join me this year. There is no cost for this; you can register for free and participate in as many of these upcoming sessions as you like.

To register, simply click on the links in the schedule below for the sessions you would like to join.

September 16, 2019

October 21, 2019

October 25, 2019

November 14, 2019

November 15, 2019

December 16, 2019

December 19, 2019

January 13, 2020

January 17, 2020

February 10, 2020

February 13, 2020

February 28, 2020

March 6, 2020

April 7, 2020

April 9, 2020

May 11, 2020

May 15, 2020

If you would prefer to arrange a private interactive videoconference for your class or school only, simply click here to schedule an online author visit. I look forward to seeing your students online!

Funny poetry is a style of poetry in it’s own right, different from the many other types of more serious verse. A style of poetry is often called a genre (pronounced ZHAHN-ruh). Other styles, or genres, include love poetry, cowboy poetry, jump-rope rhymes, epic poetry (really, really long poems), and so on.

In addition to styles or genres of poetry, there are also poetic forms. A form is a particular type of poem with rules for how to write it. For example, you may have heard of a limerick or a haiku or an acrostic. These are poetic forms, and there are rules you can follow to write them.

In chapter 6 I discuss some of the traditional forms for funny poetry, such as limericks, clerihews, funny haiku, and so on. Each of these traditional forms has rules describing how many lines it must be, how many syllables it must contain, or what the poem can be about.

In this chapter, however, I’ll show you some of the common types of funny poetry that don’t have traditional names, and don’t have so many rules you have to follow. While there are as many types of funny poems as there are poets writing them, and any one poem may contain features of several different kinds, there are some types of funny poems you will see again and again. These include:

Keep reading and you will see how you can create your own versions of these popular types of funny poetry.

The opposite, reverse, or backward poem is a poem in which everything you normally expect is reversed. For example, if you wear your hat on your feet and your shoes on your head, you’ve got the beginnings of great a backward poem.

Backward poems are easy to write. All you have to do is make everything wrong. Purple bananas. Green stop signs. Three year-old parents. And so on. Let’s try a few. Here is the beginning of a poem about some backward people who live in a backward town.

The backward folks in backward town

live inside out and upside down.

They work all night and sleep all day.

They love to work and hate to play.

The parents there are three years old.

They save their trash and dump their gold.

They fly their cars and stand on chairs.

They comb their teeth and floss their hairs.

Now it’s your turn. See if you can write another stanza about the backward folks in backward town. What else do they do backward? Do they watch TV by turning it off? Do they cook dinner by putting it in the freezer? You decide.

Here’s another one.

My name is Mr. Backward.

I do things in reverse.

I’m happy when I’m crying.

I’m better when I’m worse.

My shoes are on my shoulders.

My hat is on my toes.

I smell things with my fingers.

I write things with my nose.

Now you try it. Tell me more about Mr. Backward. What other crazy things does he do? Does he wear a suit to bed and pajamas to work? Does he eat dinner in the morning and breakfast at night? It’s all up to you. You decide what silly things you want Mr. Backward to do and then write them down.

How one more reverse/backward poem? This one will be about a person who does everything in reverse. But strangest of all, she also talks backward!

This one is a little harder than the other two, because every line in the poem is backward. But let’s have a look at it first, and then I’ll show you how it’s done.

Betty Backward is name my.

Reverse in but speak I.

Crazy I’m think just might you

Converse I how hear to.

Not only is this poem about a person who is a little bit backward, everything she says is completely backward as well. If you read each line backward, you will discover a whole new poem!

So how do you write a poem like this? It’s actually easier than it looks. First you write a normal poem, and then you reverse the lines. There’s just one more rule: Because the poem needs to rhyme after it’s reversed, you also need to rhyme the first words of your lines. The first words of your lines will end up being the last words when your poem is reversed.

Let’s add another stanza to the poem about Backward Betty, and I’ll show you how to do it. First let’s write it forward, here’s the first line of the new stanza.

No one understands me.

Notice that the first word of this line is “no.” That means our next line needs to begin with a word that rhymes with “no.” Let’s try “so.”

So they think I’m strange.

Now let’s add two more lines with rhyming first words, where the last word of the second line rhymes with “strange.”

My speech may be confusing,

but I know I’ll never change.

Lastly, let’s put it all together and then reverse it. Here are both stanzas together.

Betty Backward is name my.

Reverse in but speak I.

Crazy I’m think just might you

Converse I how hear to.

Me understands one no.

Strange I’m think they so.

But confusing be may speech my.

Change never I’ll know I.

Now that you know how to do it, see if you can add one or two more stanzas of your own to Backward Betty. Have fun!

What’s a tongue twister? A tongue twister is a poem that is nearly impossible to read without tripping up as you recite it. You’ve probably heard of “rubber baby buggy bumpers” or “she sells seashells by the seashore.” As they say, “try to say that three times fast.” Chances are your tongue won’t be able to do it.

So how do you write a tongue twister? How do you write a poem that is guaranteed to trip up all but the most careful reader? It’s not that hard, actually. All you need to do is make a list of words that sound a lot alike and then putting them together.

For example, let’s take “sea sells seashells by the seashore” and see if we can’t come up with a few more words that sound like “she sells” and “seashells.” How about these:

Next, why don’t we give this girl a name? Let’s call her Shelley Sellers. So where, by the seashore, would Shelley Sellers sell her shells? How about Shelley’s Seashell Cellars? So here we go.

Shelley Sellers sells her shells

at Shelley’s Seashell Cellars.

Now we know who she is and where she sells her shells, but who buys them? Who is Shelley selling shells to? Let’s look at our list of words. Smelly rhymes with Shelley, and dwellers rhymes with Sellers, so what if she sells her shells to smelly seashore dwellers?

She sells shells (and she sure sells!)

to smelly seashore dwellers.

What makes a tongue twister hard to say is the fact that it has lots of similar, but slightly different sounds. For example, “She sells seashells by the seashore” has a lot of “s” and “sh” sounds, as well as both long and short “e” sounds. In fact, “she sells” is the reverse of “seashells” in terms of the sounds. This makes it somewhat confusing to say; it trips up the tongue.

If you keep going with this idea of lots of “s” and “sh” sounds, you could create an entire tongue twister poem, perhaps something like this:

Smelly dwellers shop the sales

at Shelley’s seashell store.

Salty sailors stop their ships

for seashells by the shore.

Shelley’s shop, a shabby shack,

so sandy, salty, smelly,

still sells shells despite the smells;

a swell shell shop for Shelley.

But “s” and “sh” aren’t the only sounds you could repeat a lot to trip up the reader’s tongue. Using lots of words with “b” and “g” sounds, you might write a poem about someone named “Gabby” who bought a “beagle” that “begged” for “bagels.”

Gabby bought a baby beagle

At the beagle baby store.

Gabby gave her beagle kibble

But he begged for bagels more.

Or maybe with “s” and “z” sounds, you could write about someone named “Suzie” who like to “snooze” in “zoos.”

Suzie likes to snooze in zoos.

Suzie chooses zoos to snooze.

Or with “sh” and “ch” sounds, you might write about a “ship shop” that sells “shrimp ships” and a “chip shop” that sells “shrimp chips.”

Slim Sam’s Ship Shop

sells Sam’s shrimp ships.

Trim Tom’s Chip Shop

sells Tom’s shrimp chips.

See what I mean? Now it’s your turn. See if you can come up with a line or two that are particularly hard to say, make them rhyme, and you’ve got a tongue twister poem!

Repetition means repeating words, phrases, lines, or entire stanzas in a poem. Using repetition in a poem can make it easier to read and remember.

One of the easiest ways to use repetition in a poem is to repeat the first words of every line or every other line. For example, you might start each line with something like, “When I was young…” or “Have you ever seen…” or “I hope I never…” or “I wish that I…”

Long before I became a poet, way back when I was in college, one of my teachers asked the class to write a repetition poem, and this is what I turned in:

Once I was a queen bee, but I had a case of hives.

Once I was a golf ball. That was how I learned to drive.

Once I was an ocean. I liked waving at the beach.

Once I was an apple. I was pretty as a peach.

Once I was a jellyfish, until I had to jam.

Once I was a cracker, and I only weighed a gram.

Once I was a cornfield, getting lost inside the maze.

Once I was I forest. Now I’m pining for those days.

I’ll admit it’s pretty silly. Each begins with me imagining something ridiculous that I used to be, and ends with a pun of some sort, just as we discussed in Chapter 4.

Why don’t you try picking a few words and using them at the beginning of each line of a poem?

You can also repeat entire sentences throughout a poem. For example, imagine a person who thinks they are beautiful, though maybe they are not quite as pretty as they think. You might then use the line, “I think I’m rather beautiful” throughout the poem, like this:

I think I’m rather beautiful.

My head is flat and square.

I think I’m rather beautiful.

My ears grow curly hair.

I think I’m rather beautiful.

I’ve wrinkly purple skin.

I think I’m rather beautiful.

I’ve mushrooms on my chin.

Can you think of a few more ways to describe this person? What about the feet? Are they size 23? The knees? The hands? The lips? Think about it and then add another stanza. Or two. Or three. When you are all done describing this unusual person, find a way to end your poem, perhaps like this.

I think I’m rather beautiful.

My nose is long and blue.

I think I’m rather beautiful.

I hope you think so too.

You might notice this is also a “backward” poem, because this person is the opposite of what they think they are. Remember what I said earlier: any one funny poem may contain features of several different types.

Many famous poets, including authors such as Shel Silverstein, Jack Prelutsky, and even Dr. Seuss have written funny list poems. A list poem usually consists of three parts, a beginning, an ending, and a long list of things in the middle.

For example, take a look at my poem “My Parents Sent Me to the Store.”

My parents sent me to the store

to buy a loaf of bread.

I came home with a puppy

and a parakeet instead.

I came home with a guinea pig,

a hamster and a cat,

a turtle and a lizard

and a friendly little rat.

I also had a monkey

and a mongoose and a mouse.

Those animals went crazy when

I brought them in the house.

They barked and yelped and hissed

and chased my family out the door.

My parents never let me

do the shopping anymore.

You’ll see that the first two lines are the beginning, the last six lines are the ending, and everything else is the list in the middle.

One way to get started with list poems is to take a list poem that someone else has written and see if you can add another stanza or two to the list in the middle. Since “My Parents Sent Me to the Store” is all about animals this child brought home, and each stanza has two rhyming words, you would just need to think of two more animals that rhyme. For example, you might rhyme fox and ox, or goose and moose, or eagle and beagle, or snail and whale, and you might come up with something like this:

I came home with a goldfish,

and a guppy, and a goose,

an eagle and a beagle

and a mammoth and a moose.

You can also write a list poem from scratch by following these steps:

Today I decided to write a list poem about clothes. I can think of rhymes like shirt/skirt, boots/suits, bows/hose, caps/wraps, and so on. Now I just need a beginning and an ending and I can start working on my list. How’s this?

Wherever Dressy Bessie goes,

she always wears too many clothes.

That sounds pretty good to me. Now I can make a list of all the clothes she wears, like twelve pairs of slacks, eighteen shirts, thirty-seven hats, and so forth. For an ending, I’ll need to think of what would happy to Dressy Bessie with all these clothes on. Maybe she can’t stand up any longer, or she can’t squeeze through the door.

Now Bessie can’t fit through the door.

She never goes out anymore.

Now all I need is my list, like this:

Wherever Dressy Bessy goes,

she always wears too many clothes.

She puts on six or seven shirts,

eleven hats, and twenty skirts,

a half a dozen anoraks,

a pair, or two, or three of slacks.

She even wears eight pairs of boots,

and sixty-six seersucker suits.

Now Bessy can’t fit through the door.

She never goes out anymore.

Why don’t you see if you can add a few more lines to this poem. Perhaps you can use some of the rhymes I didn’t, like bows/hose or caps/wraps.

Or maybe you could come up with your own list poem with some rhyming foods, animals, or something else.

Another popular way to write funny poems is to take old poems that you already know and change them to make them funnier. The easiest way to do this is with Mother Goose nursery rhymes. It only takes a few steps:

Let’s take Humpty Dumpty as an example. This old nursery rhyme goes:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall.

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men,

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

As you can see, “wall” rhymes with “fall” and “men” rhymes with “again.” But what if we put Humpty somewhere other than the wall? Maybe he sat in a tree, or on a cat, or on the moon. Then we might rhyme tree with bee, or cat with hat, or moon with June, and we might end up with something like this:

Humpty Dumpty sat in a tree.

Humpty Dumpty got stung by a bee.

He fell out and hit his head,

And now he thinks his name is Fred.

Or maybe something like this:

Humpty Dumpty went to the moon,

To eat in the restaurant they opened last June.

He said, “All the food is delicious up here.

I just wish the restaurant had more atmosphere.”

What about Mary Had a Little Lamb? If we changed it to make it funnier, we might end up with something like this:

Mary had a little yam,

with stuffing, gravy, pie and ham.

Now Mary isn’t any thinner.

Welcome to Thanksgiving dinner.

Now you try it. Pick your favorite nursery rhyme, locate the rhyming words, change them for something else, and come up with a brand-new funny poem of your own.

In this chapter, you learned a few different ways to write funny poems, but there are many, many more. In the next chapter, we will look at some of the traditional forms of poetry that can be used to create funny poems, including limericks, clerihews, and even funny haikus.

[ Overview | Online Assemblies | Testimonials | Availability | Funding | FAQ | Prep Kit ]

Update: I will not be doing any in-person author visits during the 2021-22, and 2022-23 school years. During these two years, I will continue to provide online author visits. Update: I will not be doing any in-person author visits during the 2021-22, and 2022-23 school years. During these two years, I will continue to provide online author visits.

Each year I “visit” hundreds of schools each year via the Internet, using Zoom, Skype, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams, WebEx, and other online videoconferencing software. Online author visits are live, online, interactive videoconference presentations, that require only a PC, Mac, or iPad with a broadband Internet connection. I can present to any number of students in each session, limited only by your space and equipment (projector, speakers, etc.) Book Now!You can book an online author visit with me right now by clicking the ‘Click to Schedule’ button. If you would like more information, please fill out the form at the bottom of this page. Pricing

Benefits of Zoom online author visits

Online ProgramsMy online classroom visits are normally 45-minutes long, and typically include 15 minutes of presentation, 15 minutes of writing with your students, and 15 minutes of Q&A. In addition, I also have special programs available on the following topics:

Would you like to see a program that isn’t listed here. Please just let me know. I can also create a custom presentation for your school. Sign Up NowI offer sessions for grades K-2, 3-6, 6-8, and 7-12. Check my calendar for availability. Any date not otherwise marked as is most likely available. Dates already marked with a Skype visit to another school are almost definitely available. To sign up, simply fill out the form below and I will contact you to get you set up. If you would prefer a different date or time than what is listed on my calendar, please just let me know. |

Fill out this form to receive more information about Kenn Nesbitt’s in-person and online school and library visit programs.

[ Overview | Testimonials | Availability | Funding | FAQ ]

Would you like to get your students excited about reading and writing? My online author visits are high-energy, engaging, educational, and, above all, funny! Your students will have so much fun laughing, they will come away with a desire to put pencil to paper and visit the library. Would you like to get your students excited about reading and writing? My online author visits are high-energy, engaging, educational, and, above all, funny! Your students will have so much fun laughing, they will come away with a desire to put pencil to paper and visit the library.

Each year I visit hundreds of schools each year via the Internet, using Zoom, Skype, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams, WebEx, and other online videoconferencing software. Online author visits are live, online, interactive videoconference presentations, that require only a PC, Mac, or iPad with a broadband Internet connection. I can present to any number of students in each session, limited only by your space and equipment (projector, speakers, etc.) Book Now!You can book an online author visit with me right now by clicking the ‘Click to Schedule’ button or scanning the QR code. If you would like more information, please fill out the form at the bottom of this page.

Pricing

Benefits of Zoom online author visits

Online ProgramsMy online classroom visits are normally 45-minutes long, and typically include 15 minutes of presentation, 15 minutes of writing with your students, and 15 minutes of Q&A. In addition, I also have special programs available on the following topics:

Would you like to see a program that isn’t listed here. Please just let me know. I can also create a custom presentation for your school. Sign Up NowI offer sessions for grades K-2, 3-6, 6-8, and 7-12. Check my calendar for availability. Any date not otherwise marked is most likely available. Dates already marked with another online visit to another school are almost definitely available. To sign up, either click here or fill out the form below and I will email you to get you set up. If you would prefer a date or time that may not appear to be available on my calendar, please just let me know. |

Fill out this form to receive more information about Kenn Nesbitt’s online school and library visit programs.

Beginning in 1996, April has been declared National Poetry Month in the US. This tradition was started by the Academy of American Poets to celebrate poets and the wonderful things that poetry can bring to our lives.

There are plenty of ways for kids to celebrate National Poetry Month. Here are a few suggestions to get you started: