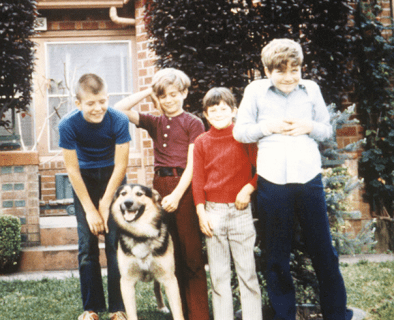

Can you guess which one is me?

I was nine years old when my family went water-skiing every day for an entire summer. We’d get up early, fix enough sandwiches to fill the cooler, and head for the lake in our midnight blue 1967 Cadillac Coupe de Ville, ski-boat in tow. On the best days, we would arrive before the wind had kicked up, when the lake was still a glassy calm.

Somehow, my dad’s job with a heating and air conditioning company allowed him to work mainly in the spring and fall. With summers free, my parents took us to the lake every day; me and my two brothers, Hap and Danny, and our friend Jimmy. Hap was the one with the crew-cut. Danny looked just like me, only more devious. We were all skinny, tanned, and a little too wild.

This was 1971, and the car had only an AM radio. No FM, no 8-track player, and certainly no DVDs or video games. A trip to the lake meant over an hour in the car each way, along winding mountain roads where the AM radio was useless, there weren’t enough other cars to play “slug bug,” and thumb wrestling got old in a hurry. Eventually–as four boys will do when stuck in the back seat of a car for an hour or two–we would begin to fight. It always started innocently enough with a “Quit touching me,” or a “Hey, that’s mine,” but would quickly erupt into a full-blown wrestling match on the floor of the car. Did I mention we also didn’t have seat belts?

My parents must have figured out early on that summer that they were the entertainment. I suppose they realized that if they didn’t keep us busy and focused, we would eventually start fighting just to have something to do.

They made up games. They told stories. They sang songs. And they recited poems. I still don’t know how, but my dad had committed a great many poems to memory. He could recite “Casey at the Bat,” “The Raven,” “Dangerous Dan McGrew,” or any of a half dozen other rhyming narratives at the drop of a hat, keeping us from beating on one another for the next ten minutes, at least.

One of the poems that absolutely fascinated me was a bit of nonsense verse I later found out was called “The Dying Fisherman’s Song.” It begins: “Twas a summer’s day in winter / the rain was snowing fast / as a barefoot boy with shoes on / stood sitting on the grass.”

I was also entranced with the equally ridiculous “One fine day in the middle of the night, two dead men got up to fight,” and “Ladies and jellyspoons, I come before you to stand behind you to tell you of something I know nothing about.”

I was hooked. I recited these lines in my head over and over, week after week, until they burned new electrical pathways in my brain. If someone had given me Shel Silverstein’s “Where the Sidewalk Ends” (not possible, since it wasn’t published until 1974), I would have dived into it and never come out.

I did what any 9-year-old funny poetry addict would do, given the circumstances: I read MAD Magazine. No, that’s understating it. I devoured MAD Magazine. I was smitten with their parodies of songs and poems, and I owe a debt of gratitude to its publisher, Bill Gaines, for creating such a perfect periodical for nerdy 9-year-old boys.

It wasn’t until I was 20 years old that I first heard of Shel Silverstein, and I was nearly 30 before I discovered that he wrote poetry. At 32–well-primed by Shel’s first two “big books”–I happened upon the poems of Jack Prelutsky and Ogden Nash, and I fell in love with funny children’s poetry all over again. It’s a love affair that continues to this day, 17 years and 10 books (of my own) later.

So the moral of the story, gentle reader, is this: Read to your kids. Sing to your kids. Recite poetry for your kids. Be silly with your kids! It may make all the difference. It did for me. Thanks, Dad. Thanks, Mom.